ART/STYLE/TRAVEL

Now Dig This: The Ken Johnson Kerfuffle.

December 4, 2012 · 0 Comments

Source: C-Monster

Above: Ghetto Merchant, ca. 1965, by John Riddle. Part of Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-80, on view at MoMA PS1, and the subject of one heck of an unsavory review in the New York Times. (Image courtesy of the Hammer Museum and the collection of Claude and Anne Booker.)

By Carolina A. Miranda:

Last month, Ken Johnson, an independent writer who serves as an art critic for the New York Times, published a review of Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-80, on view at MoMA PS1. The piece was critical of the show on a number of points, most notably that many of the works promoted a racial solidarity that could be alienating to white viewers. There are also some very uncomfortable paragraphs about the ways in which Black artists have employed the medium of assemblage:

“[Marcel] Duchamp’s work is a piece of deracinated, intellectual mischief-making designed to question relations between language and reality. [John] Riddle’s is about a particular population of people digging itself out of a real-world debacle.”

Something that could easily be read as: the sculpture by the white-guy European artist addresses universal themes; the piece by the Black artist, not so much. (If you haven’t read Johnson’s piece, I’d suggest clicking over and giving it a gander before you keep reading.)

That review, in addition to a preview produced by Johnson (about a show of women artists in Philly), has since generated an anonymous online petition/open letter directed at the New York Times. “Using irresponsible generalities, Johnson compares women and African-American artists to white male artists, only to find them lacking,” reads the opener. It goes on to state:

“Rather than engage the historical work in the exhibition, Mr. Johnson states that he prefers the work of mostly contemporary black artists who have been widely validated, without acknowledging the social progress over the last 50 years that might allow for the next generation of artists to ‘complicate how we think about prejudice and stereotyping.’”

It asks that “the Times acknowledge and address this editorial lapse and the broader issues raised by these texts.” As of this writing, the petition has garnered almost 1,000 signatures, including prominent art world figures such as Glenn Ligon and Coco Fusco, who confirmed to Artinfo’s Julia Halperin that they did indeed sign it.

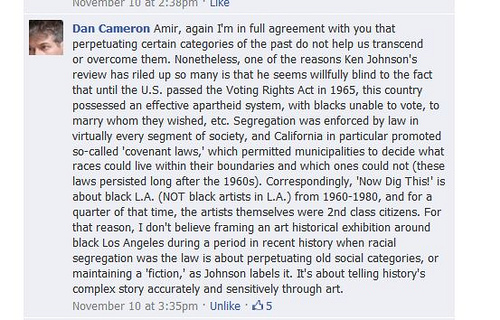

Earlier this month, Johnson’s review also generated a raft of lengthy partially-deleted/disappeared discussions on his Facebook page, which includes posts by Kara Walker, as well as curator Dan Cameron, both of whom challenge his conclusions in very articulate ways. The discussions were in turn heated, articulate, rancorous, illuminating and all kinds of internet crazy pants. (I’ve posted some of the most interesting outtakes after the jump, but if you need some interesting reading the whole mucky schmegagie can be worthwhile.)

+++

Now Dig This! was organized by independent curator and scholar Kellie Jones and originally debuted at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles last year as part of the Pacific Standard Time (PST) series of exhibitions. It was very well-received. In fact, Johnson’s colleague, Roberta Smith, described it as having “a visionary power.” It was the only PST show to travel to New York.

I personally dug Now Dig This! Among all the shows I saw during PST (and I saw a lot of them), this was one of the three that most stuck with me. It was an introduction to artists and works with whom I had only cursory familiarity. It provided an important sense of lineage for the work of contemporary artists such as David Hammons. It revealed a lot about the region that I grew up in and that I thought I knew. And it provided an important social, geographic and political context for a group of artists who, for a variety of reasons related to race and class, did not have the luxury of being included in the Ferus Gallery scene.

Johnson’s review is problematic for a variety of reasons. Not the least of which is that he appears to be prickly about shows that take as their organizing principle the race or gender of the artist — and he employs the work of white artists as the ultimate gold standard. As with Now Dig This!, he gave a skewering to the LACMA-organizedPhantom Sightings, which examined art made in the wake of the Chicano movement, railing ainst the idea of the “identity-based show” as an “evil whose necessity would disappear in a more equitable world.” Likewise, in his review of Seductive Subversion, the exhibition of women pop artists held at the Brooklyn Museum two years ago, he judges the work against the production of male pop artists. (Sample line: “If it does represent the best female artists of the first Pop Art generation — and there is no reason to think otherwise — you’d have to admit that there were no women producing Pop Art as inventively, ambitiously and memorably as their male counterparts. That is not to say, however, that there were no interesting women mining the Pop vein.”) His listing for The Female Gaze, in Philly — the one that also happened to draw the ire of the petition writer — makes a similar comparison between the production of male and female artists.

To be fair, when reviewing individual artists, this doesn’t seem to be an issue. In a review of a show of Kara Walker’s art in 2003, he addresses her aesthetics and her message straight on. In a piece covering an exhibition of sculpture by Anne Truitt, he does much the same. And although it contains a few catty lines, he generally enjoyed an exhibition of feminist video that went on view at the Brooklyn Museum in 2009.

But there nonetheless seem to be some issues at work here. In one of the various Facebook posts that went up during the long discussion of his review, Johnson stated, “Personally, I think race is a fiction that far too many take as real, which, as a consequence, makes it all too real.” It was something that was echoed in his book on art and drug consciousness, in which he discusses pieces that get at the illusory nature of race. (I’d quote from the book, but I’m in the middle of moving and everything’s in storage, so I’m asking y’all to trust me.) And there are some statements he made about Black artists and solidarity at a panel of art writers in New York earlier this month — in which he alludes to his Now Dig This! review — which would seem to imply that he finds shows built around racial solidarity difficult to criticize because they are more about moral righteousness than anything else. (It’s not a direct transcript, so draw your own conclusions on that last one.)

Johnson is right in that race is a fictional concept. There is no biological basis for racial classifications. We all have the same teeth and heart and lungs, even if we come in different shades. But the social and political structures that race generates imbue every aspect of our society, not to mention our history: slavery, indentured servitude, apartheid, Jim Crow, housing covenants. As a result, race shapes experience and world view — and therefore art. To not recognize this is a gross omission. Race can determine a person’s economic status, their social status, even where they live. And in a society that is obsessed with it, it is a perfectly valid lens with which to examine art.

I will admit that there are identity-based and gender shows that are sloppy and uninteresting, exhibitions in which some curator seems to be saying, ‘It’s Hispanic heritage month, let’s put a bunch of Latinos in a room.’ But Now Dig This! and Phantom Sightings were the opposite of that. These rigorous, well thought-out exhibitions tell a story about a place and time. Now Dig This! provided historic and material context for a group of artists whose work doesn’t generally get pride of place in museums. (Jones once told me that many of the pieces in Now Dig This! actually reside in major museum collections — but they never get shown.) Phantom Sightings addressed ways in which Chicano artists employed conceptual language in the wake of 1970s conceptual art and civil rights movements. These exhibitions connected dots that weren’t previously connected and for that reason, they are important. (For what it’s worth, I addressed some of this in a piece about Chicano art that I did for ARTnews, which was, in part, a response to Johnson’s Phantom Sightings review.)

But in his critiques, Johnson is so busy railing against the idea that there are shows built around fictional notions of race or that some piece of art might not be as good as that of some long-dead male artist, that he fails to notice that these groups of artists, in the collective, might have something interesting — even important — to say. And that as a critic, he should be listening to what that might be. At its heart, this is intellectually lazy criticism: seeing what you want to see rather than letting the art speak to you. (For a point of reference: read Christopher Knight’s reviews of the same exhibitions, here and here.)

+++

At the top of this post is an image of a sculpture by John Riddle that was made sometime around 1965. Ghetto Merchant is an assemblage crafted from cash registers that the artist rescued from a burned out store after the Watts Rebellion. In its structure, it is part Ibram Lassaw geometric monster, part musical instrument, part abstracted figure — all of it evidence of the ability of an artist to turn tragedy into something inspired. Until Jones put it on view in Now Dig This!, it sat in the home of a private collector and was rarely, if ever, seen by the public. And there were so many other pieces like this in that show. Melvin Edwards’ torqued industrial wall sculptures left me feeling suffocated. Senga Nengudi’s pantyhose installations grabbed me by the tubes, then twisted and yanked them in aggressive, uncomfortable, hilarious ways. Noah Purifoy transformed the basest junk into something greater than its parts.

It’s too bad Johnson missed this — all because he was so focused on race. That is, any race that isn’t white.

And now, for some excerpts from the Facebook discussions. Please keep in mind these are excerpts, and not the full discussion — which contained hundreds of comments. You can find that here.

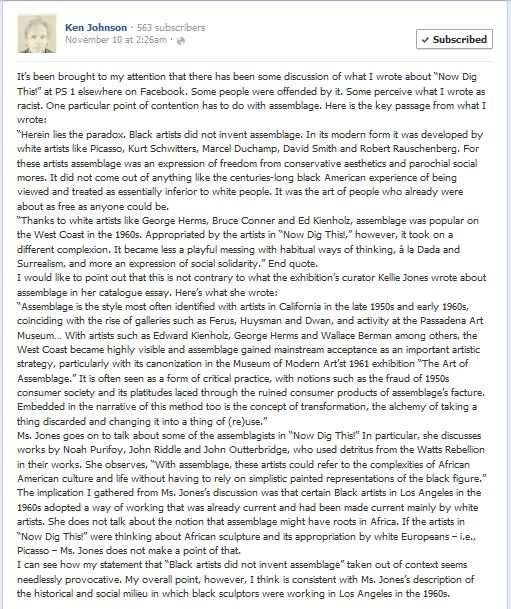

Johnson’s initial post:

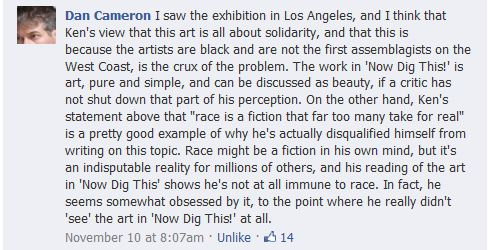

Many posts down, Dan Cameron posts:

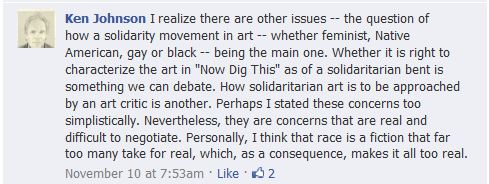

Much later, a follow-up from Johnson, making the statement that “race is a fiction”:

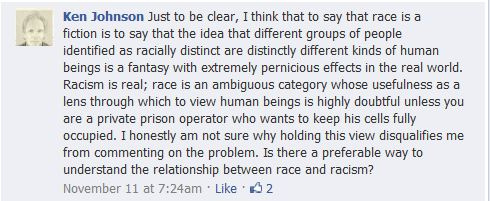

Afterwards, a clarification:

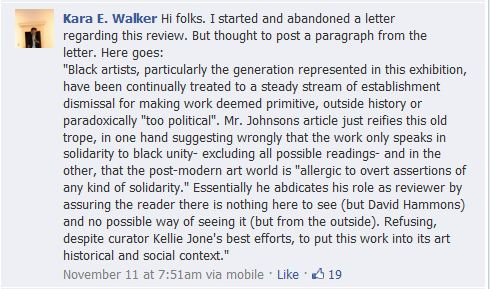

At one point, a post from Kara Walker:

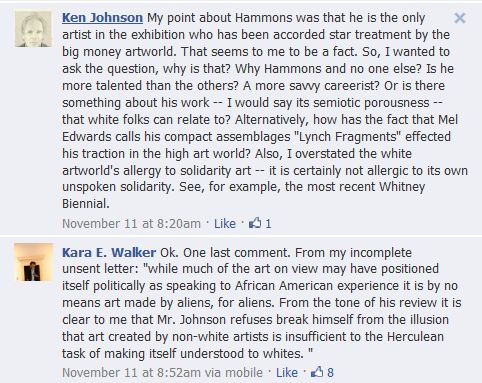

An exchange between Johnson and Walker:

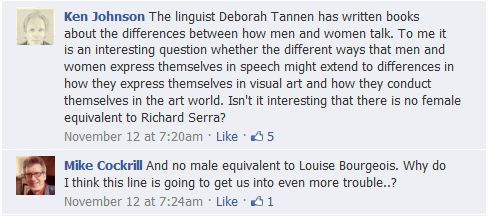

And on to the subject of women:

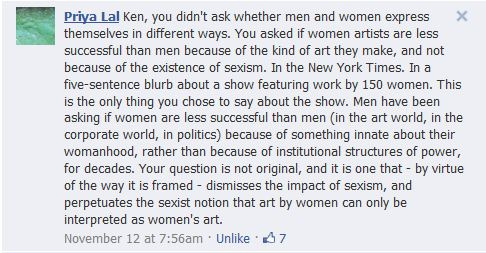

A commenter named Priya Lal responds:

And Dan Cameron makes a point to a commenter, on his own Facebook feed, about why Now Dig This! was important:

By admin

Readers Comments (0)

Recommended links

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Migliori Siti Casino Online

- Lista Casino Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Paris Sportif Crypto

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Online Non Aams

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- UK Casino Not On Gamstop

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Fiable

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne En Belgique

- Scommesse Italia App

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- 코인카지노

- 파워볼사이트

- лучшие казино Украины

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino Online Senza Documenti

- Migliori Siti Scommesse Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino Non Aams

- Lista Casino Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne France Légal